Tim Scudder, PhD

The Strength Deployment Inventory 2.0 (SDI 2.0) is an assessment of human motives and strengths. It stands on the foundation of practical application, scholarship, and research that began with Elias Porter’s introduction of the SDI in 1971 and publication of Relationship Awareness Theory (Porter, 1976). The theory has roots in psychoanalysis (Fromm, 1947) and client-centered therapy (Porter, 1950; Rogers, 1951, 1961).

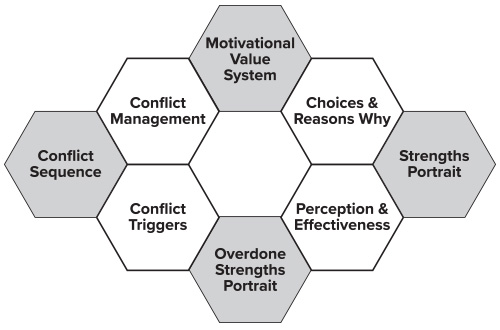

Today the SDI 2.0 offers four views of a person: a Motivational Value System, a Conflict Sequence, a Strengths Portrait, and an Overdone Strengths Portrait. These four views form a systems view of personality and productiveness at work. When personality is considered in the context of relationships, and viewed as a dynamic system, greater explanatory power is available than when personality is viewed as independent variables or dichotomies (Lewin, 1935; Piers, 2000; Sullivan, 1953). In a systems view, the conscious interaction of emotional states, behavior, and motives is an advancement from classic psychoanalytic theory, which holds that motives and drives are largely relegated to the unconscious (Meissner, 2009).

To fully understand the methodology and meaning of the SDI 2.0 assessment, the purpose of the assessment must be considered. The SDI 2.0 is based on foundational concepts that lead to specific types of measurement (data collection), scoring, reporting, validity and reliability testing, and the application of assessment results.

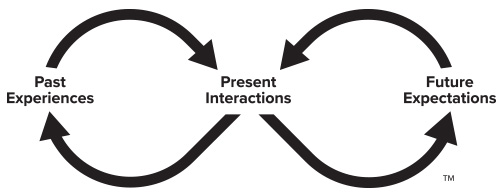

The purpose of the SDI 2.0 is to improve the quality of working relationships. People have relationships within themselves, with each other, and with their work. Relationships are psychological connections over time; they have history, the present moment, and expectations for the future (Figure 1). Improving relationships requires beginning with self-awareness. Increased self-awareness results from greater conscious understanding of the true self, and the reduction or removal of defenses against self-understanding. Greater self-awareness enables more clear and accurate understanding of others.

Relationship Intelligence is the application of knowledge in specific settings or contexts to produce results that are meaningful to people in relationships.

Relationship Intelligence helps people to:

These skills are essential to creating collaborative communities that foster learning, development, and authentic connections to others and to work.

Figure 1

Relationship Intelligence Model

Personality is broadly defined as the set of stable tendencies and characteristics that influence people’s thoughts, feelings, and actions across all types of situations (Maddi, 1996; Weiner & Greene, 2008). Personality is not easy to classify. As Kluckhohn and Murray (1948) noted, every person is like every other person in some regards; every person is like some other persons in some regards; and every person is unique in some ways. Personality types are the result of theory and analysis that describe that middle ground, the way that people share characteristics with some, but not all, other people. The assignment of a type to a person as the result of a personality assessment in no way invalidates the uniqueness of a person. Instead, it helps to provide a frame of reference to anticipate people’s thoughts, feelings, and actions. People with the same personality type may still have uniquely personal traits.

Motives are the primary determinants of personality types described by SDI 2.0 results. There are three primary motives, which are experienced differently in two emotional states: 1) when things are going well and 2) when there is conflict. Motives are purposive in nature; they are the underlying drives or reasons that energize a person to think, feel, or act in various ways as they relate to others.

Three primary motives are present in every person in both conditions, but in varying degrees. When things are going well, three primary motives work together in each person to form a Motivational Value System. When people experience conflict, these motives take on a different quality and are accessed in a predictable pattern, termed a Conflict Sequence. Table 1 shows the three motives under two conditions, along with the color-codes and keywords that are used in SDI 2.0 assessment results.

Table 1

Motives in Two Conditions

Motives | Color | Well State Keyword and Meaning of Motive | Conflict State Keyword and Meaning of Motive |

|---|---|---|---|

Nurturant | Blue | People Actively seeking to help others | Accommodate Drive to preserve or restore harmony |

Directive | Red | Performance Actively seeking opportunities to achieve results | Assert Drive to prevail over another person or obstacle |

Autonomous | Green | Process Actively seeking logical orderliness and self-reliance | Analyze

Drive to conserve resources and assure independence

|

Fulfilling a motive in a well-state contributes to feelings of self-worth, while the restriction of a motive in a well-state may trigger a shift to the conflict state. Fulfilling a motive in the conflict state can trigger a return to the well state, but the restriction of a motive in the conflict state may trigger a shift to another stage of conflict. The connections between these two independent states create a large number of dynamic types, which are further explained in the report generation section.

The SDI 2.0 presents a prioritized set of 28 strengths to each respondent. Strengths are behaviors that are driven by underlying motives and productive intentions. Strengths are generally valued and appreciated in the context of relationships. The 28 strengths (and their overdone counterparts) in the SDI 2.0 should be viewed as part of an overall personality theory. Elias Porter’s initial work with strengths was inspired by Erich Fromm’s (1947) lists of positive and negative aspects of personality types. Porter refined the lists of strengths through his own research and practical application. More recent research (Scudder, 2013) drove further changes to the 28 strengths that improved their validity, reliability, and usefulness in the present version, the SDI 2.0.

Strengths may also be viewed as traits. Each strength has a connection with motives and personality type. But strengths, because they are behaviors, are freely chosen by people as they consider their situations, goals, and relationships. Desires and beliefs help to explain action and give it meaning (Rosenberg, 2008). The application of strengths is variable across situations. There are correlations with personality, but strengths alone are not the essence of personality. Instead, strengths are the ways that individuals express their core motives through action.

The SDI 2.0 also presents a prioritized set of 28 overdone strengths, which are the non-productive counterparts to the strengths (Fromm, 1947). Because strengths are driven by motives, and motives are purposive, people expect their strengths to produce desired results. When desired results are not achieved, people may try a little harder, with the expectation that more effort with the same strength will produce the desired result. This is how people can sometimes get over-invested in their strengths, to the point that an overdone strength can limit their effectiveness or create tension or conflict in relationships.

Bringing awareness of the implications, or effects, of overdone strengths to people helps them manage the frequency, duration, intensity, or context (Livson & Nichols, 1957) of the behavior for greater effectiveness. It also helps them make more informed decisions about what other strengths they could use in various situations and relationships. SDI 2.0 results bring overdone strengths into conscious awareness and gives people the power to improve their relationships and their effectiveness.

In addition to reviewing the methodology and summarizing relevant past research, the present study reports the results of 12,565 SDI 2.0 assessments. The population is comprised of working adults, predominantly from large, multinational, US-based corporations, who participated in Core Strengths Results through Relationships training programs in late 2018 and early 2019. No data regarding age, gender, ethnicity, or other demographics were collected, and no effort was made to control for other mediating variables such as role or industry.

The methods of collecting data are influenced by the underlying phenomena to be measured and the application to which the results are to be used. Given the focus on motives as the primary determinants of personality, and that personality is stable across all types of situations, the motives section of the SDI 2.0 asks people to assume a whole-life perspective and think about themselves in all types of situations as they complete the assessment. The strengths section requires that the respondent adopt a change in mindset. Given that strengths are behaviors, and therefore not necessarily consistent across situations, respondents are directed to think about workplace situations when they complete the strengths section of SDI 2.0. This is because the results from the strengths section of the assessment are used primarily in work situations, but need to be connected to the underlying personality and motives of the person doing the work.

The motives section of the SDI 2.0 is a 60-item, dual-state, ipsative assessment. Respondents assume a whole-life perspective as they respond to two groups of items, one for each state: 1) when things are going well, and 2) the experience of conflict. Each state has three scales and the sum of scale scores for each state must be 100. Items are presented in sets of three via sentence stems that require respondents to allocate 10 points among three different sentence endings to show how frequently the different endings describe them. The range of possible responses for each item is zero to 10. The range of possible scores on each scale is from zero to 100.

The scale scores from the going well section of the SDI are used to identify one of seven personality types called Motivational Value Systems (MVS). The scale scores from the conflict section of the SDI are used to identify one of 13 personality types called Conflict Sequences (CS). Each respondent’s scores are associated with two types, an MVS and a CS. There are 91 (7 x 13) possible dynamic types.

The ipsative data collection method mirrors the underlying phenomena that it measures. Each person is assumed to have all three core motives in varying degrees. The ipsative items force respondents to allocate points in a manner that represents the interplay between the three motives. The 100 point totals, allocated among three scale scores, facilitate the presentation of results in familiar manners, such as percentages. The fact that every respondent must have the same total score also facilitates comparison between many individuals. It removes the discrepancies often associated with other methods, such as Likert scales, where some people frequently give maximum scores, but others rarely give maximum scores.

In the strengths section of the SDI 2.0 respondents assume a mindset based on their current work role and environment. The intent is to focus the respondent on the work environment, where they are most likely to apply the results of the assessment. There are 56 strengths statements, which respondents rate using a five-point Likert scale. Statements are presented in sets of four; each set has a strength that correlates to the Blue, Red, Green, and Hub MVS types. There are 14 sets of four statements, seven of which are productive statements of strength, and seven of which contain non-productive, overdone statements. Within each set, respondents must first choose 1 through 5 from Likert scales. Then, if two or more items are rated equally high or equally low, forced-choice tiebreakers are presented. This method ensures that respondents must choose one statement that is most like them and one statement that is least like them from every set of four. Each set of four statements yields six data elements, the four Likert-scale responses, and an ipsative component that identifies the in-set statements that are most-like, and least-like the respondent. A proprietary scoring algorithm is applied to the responses, which yields an ordinal ranking of 28 strengths, and 28 overdone strengths.

Ipsative, Likert-scale, and forced-choice data collection methods produce ordinal, not interval, data. Respondents’ scores indicate preferences or relative weightings among possible responses, but the preferences (even on Likert scales) do not have fixed intervals. For example the difference between 2 and 3 on a Likert scale is not exactly the same as the distance between 3 and 4. In fact two items could have a response of 3, but on one the respondent could have wavered between 2 and 3, while they wavered between 3 and 4 on the other. In this case, the two responses of 3 are not equal from a psychological perspective. However, research conducted with a Likert scale version of the SDI demonstrated a strong positive correlation with the ipsative version’s scales (Barney, 1996).

Parametric methods are meant to be applied to interval data, and non-parametric methods applied to ordinal data. But parametric methods yield similar results to non-parametric methods when applied to ordinal data, especially with large populations and when data are distributed roughly normally (Rust & Golombok, 2008; Warner, 2008). Analysis of SDI 2.0 data shows normal distributions with large population samples, therefore, parametric methods, such as the calculation of means and standard deviations, are appropriately applied to SDI 2.0 data.

The three scores from the going-well section indicate a Motivational Value System type as defined by the criteria in Table 2. These mathematical definitions correspond with regions on the SDI Triangle (Figure 2). The triangle is comprised of three scales, from 0 to 100, that intersect at 33⅓. The MVS boundaries on the triangle are set at decimal locations, which ensure that no set of scores can be on a border, because all scores must be whole numbers.

Table 2

Mathematical Definitions of MVS Types

MVS Type | Well Blue | Well Red | Well Green |

|---|---|---|---|

Blue / Altruistic-Nurturing | WB > 42.3 | WR < 33.3 | WG < 33.3 |

Red / Assertive-Directing | WB < 33.3 | WR > 42.3 | WG < 33.3 |

Green / Analytic-Autonomizing

| WB < 33.3 | WR < 33.3 | WG > 42.3 |

Red-Blue / Assertive-Nurturing

| WB > 33.3 | WR > 33.3 | WG < 24.3 |

Red-Green / Judicious-Competing | WB < 24.3 | WR > 33.3 | WG > 33.3 |

Blue-Green / Cautious-Supporting | WG > 33.3 | WG > 33.3 | WR < 24.3 |

Hub / Flexible-Cohering | 24.3 < WB < 42.3 | 24.3 < WR < 42.3 | 24.3 < WG < 42.3 |

Each individual set of three going-well scores is represented by a dot on the triangle. The location of the dot’s center is determined by the intersection of all three scores. Every point on the triangle represents a unique set of three numbers that add to 100. There are 5,151 possible locations for an MVS dot on the triangle (which is the sum of all integers between 1 and 101). If an MVS dot is within 6 points of any border (which is the test-retest reliability of the scales), additional guidance regarding the neighboring MVS region is reported. Figure 3 shows a dot in the Blue MVS with a test-retest reliability circle that crosses into the Blue-Green MVS.

Table 3

Mathematical Definitions of CS Types

CS Type | Conflict Blue | Conflict Red | Conflict Green | Other TEST(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

B-R-G

| CB > 39.3 | – | CG < 27.3 | CB-CR > 6.3 CR-CG > 6.3 |

B-G-R | CB > 39.3 | CR < 27.3 | – | CB-CG > 6.3 CG-CR > 6.3 |

B-[RG]

| CB > 39.3 | – | – | ABS(CR-CG) < 6.3 |

R-B-G | – | CR > 39.3 | CG < 27.3 | CR-CB > 6.3 CB-CG > 6.3 |

R-G-B | CB < 27.3 | CR > 39.3 | – | CR-CG > 6.3 CG-CB > 6.3 |

R-[BG]

| – | CR > 39.3 | – | ABS(CB-CG) < 6.3 |

R-[BG]

| CB < 27.3 | – | CG > 39.3 | CG-CR > 6.3 CR-CB > 6.3 |

R-[BG]

| – | – | CG > 39.3

| ABS(CB-CR) < 6.3 |

[RB]-G | – | – | CG < 27.3 | ABS(CB-CR) < 6.3 |

[RG]-B

| CB < 27.3 | – | – | ABS(CR-CG) < 6.3 |

[BG]-R | – | CR < 27.3 | – | ABS(CB-CG) < 6.3 |

[BRG] | 27.3 < CB < 39.3 | 27.3 < CR < 39.3 | 27.3 < CG < 39.3 | – |

The three scores from the conflict section indicate a Conflict Sequence type as defined by the criteria in Table 3.

The triangle has two sets of boundaries, but uses the same three scales to determine the location of an arrowhead’s point, which represents the Conflict Sequence. The mathematical definitions correspond with 13 regions on the SDI Triangle (Figure 4). There are also 5,151 possible locations for the arrowhead. Each bounded region of the triangle delineates an area where scores have the same pattern. Six regions show clear, three-stage Conflict Sequences with a different color at each stage. Three regions have a bracketed Stage 1 and 2, with a clear Stage 3. Three regions have a clear Stage 1 with brackets for Stages 2 and 3. One region, the small hexagon in the center, has a bracket including all three colors in all three stages. The brackets indicate scores that are close together. The practical significance of brackets in a Conflict Sequence is that brackets indicate a personal choice between two or more alternatives at the indicated stage(s) of conflict.

When the Motivational Value System and Conflict Sequence are presented on the SDI triangle together, the dot and arrowhead are joined by a line to indicate that the two results are associated with one person. Several individuals may be presented together on the same triangle. (Figure 5)

The three scores for the going-well scales must equal 100, as must the three scores for the conflict scales. But the two sets of scales are independent; one set does not predict or control the other. The MVS dot can be anywhere on the triangle, and the CS arrowhead can be anywhere on the triangle. Therefore, from a typology perspective, 91 dynamic types are possible (7 MVS x 13 CS). But there are many more possible arrows, because there are 5,151 points on the triangle, each of which are used twice for one arrow. This results in 26,531,801 (5,1312) possible unique arrows based on the interplay of three core motives in two affective states.

Table 4 (Scudder, 2013) shows the distribution of all 7 MVS types, all 13 CS types and the 91 possible combinations thereof. The data in this table are assumed to be roughly representative of working adults in the United States because the sample represents a broad cross section of organizations and a wide variety of applications.

Table 4

Cross-Tabulation of MVS and CS Types: Percentages

CS Type | Blue | Red | Green | Red-Blue | Red-Green | Blue-Green | HUB | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B-R-G | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.76 |

B-G-R | 4.60 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 1.39 | 0.01 | 1.69 | 1.13 | 9.19 |

B-[RG]

| 1.20 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.56 | 3.04 |

R-B-G

| 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.86 |

R-G-B | 0.31 | 2.16 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.22 | 1.59 | 6.24 |

R-[BG]

| 0.34 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.70 | 2.93 |

G-B-R

| 4.67 | 0.75 | 1.77 | 1.80 | 0.28 | 3.81 | 5.10 | 18.17 |

G-R-B | 0.83 | 1.78 | 2.11 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 3.67 | 11.51 |

G-[BR]

| 2.17 | 1.00 | 1.93 | 1.83 | 0.62 | 2.04 | 5.86 | 15.45 |

[BR]-G

| 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 1.26 |

[RG]-B

| 0.49 | 1.79 | 0.66 | 1.28 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 2.70 | 8.06 |

[BG]-R

| 3.92 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 1.61 | 0.08 | 1.93 | 3.16 | 11.66 |

[BRG]

| 1.72 | 1.18 | 0.39 | 2.16 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 4.61 | 10.89 |

Total | 20.96 | 10.56 | 8.14 | 14.74 | 3.62 | 12.43 | 29.54 | 100.00 |

n=9,798

Table 5

Line Length and Practical Significance

Line Length | Change in Motives from MVS to Stage 1 Conflict |

|---|---|

From 0 to 10 | Can be difficult to detect by self and others |

From > 10 To 25 | Somewhat noticeable by self and others |

From > 25 To – | Usually obvious to self and others |

A systems view of personality enables explanation of phenomena that are due to the interaction between independent results, as opposed to the static-state views that are most common in personality theory and testing. The connections between the MVS and the CS are used in report generation to provide additional information to respondents, such as the length of the line and ideas about how to resolve conflict. Each respondent receives one of 49 descriptions that connect the motives in one of seven Stage 1 conflict states to one of 7 MVS types as an example of conflict resolution. Each respondent also receives information about the length of the line connecting the MVS dot and the CS arrowhead, per Table 5.

Each respondent receives their individual scale scores, along and arrow drawn on the SDI triangle, which is a graphic representation of the scale scores. Explanatory text for the Motivational Value System is offered based on one of seven possibilities. Explanatory text for the Conflict Sequence is offered based on one of 13 possibilities. There are 91 permutations of explanatory text for the MVS and CS. Additional explanatory text is offered based on the whether results are close to another type, and connections between the results. All of these variables work together to inform a report generation process that describes personality as a system of motives under two conditions.

The results from the work-focused, strengths section of the SDI 2.0 are used to produce two portraits of the way respondents deploy their strengths. The Strengths Portrait, and variations of it, present the positive, productive strengths in an array from most likely to deploy to least likely to deploy. The Overdone Strengths Portrait, and its variations, similarly display the overdone strengths that may limit respondents’ effectiveness at work or cause difficulty in working relationships. Respondents’ work roles are identified on the strengths reports, but the roles are omitted from the reports that describe personality, because personality applies across multiple situations and the strengths reports are based on the work environment.

The SDI 2.0 reports 28 strengths, and 28 overdone strengths, in rank order. The data are normally distributed, and are presented to respondents in a graphical format that resembles a normal curve. The display format is derived from Q-methodology (Stephenson, 1953/1975). It shows the items of most significance in the two tails of the normal curve. Strengths (or Overdone Strengths) near the top of the portrait are most like respondents to deploy at work, and those at the bottom are least like them to deploy at work. Strengths on the same line have underlying scores that are close to each other, which suggests that respondents deploy those strengths at about equal levels. Figure 6 presents the standard portrait template, along with a transformation of the template under the normal curve.

The top strengths, and overdone strengths, are most significant. Detailed interpretive text is provided for the top strengths, while limited interpretive text is provided for the remaining strengths.

Table 6

The Methodical Strength and Example Reasons to Deploy It

Strength | Blue MVS Reason | Red MVS Reason | Green MVS Reason | Hub MVS Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Methodical I am orderly in action, thought, and expression… | …to create a structure that will benefit people. | …to establish a standard to evaluate performance.

| …to give the process a chance to work as intended.

| …to be sure we have considered all perspectives. |

SDI 2.0 results take this into account by presenting a view of strengths informed by the most likely reasons to use those strengths, based on respondents’ MVS. Table 6 shows four sample reasons to use one strength.

The number of possible variations of the Strengths Portrait and Overdone Strengths Portrait is so large that for practical purposes, the number is almost infinite. There are 28-factorial possible ordinal rankings, with 7 MVS overlays. The formula for possible permutations is therefore 7(28!). This method and systems view of personality situated in a work context ensures a truly personalized report for each respondent.

SDI 2.0 data are roughly normally distributed on all scales. Descriptive statistics for scales or results are presented in Tables 7, 8, and 9.

The motives scales descriptive statistics show that the data are roughly normally distributed and have similar patterns to prior studies (Barney, 1998; Cunningham, 2004; Porter, 1973; Scudder, 2013).

Tables 8 and 9 show the descriptive statistics for strength and overdone strength rankings. 1 represents the strength most likely to be deployed at work and 28 represents the strength least likely to be deployed at work. Both tables demonstrate that the strengths are about normally distributed across a large population.

As shown by the descriptive statistics. Large populations of SDI 2.0 data are roughly normally distributed and it is therefore appropriate to apply parametric methods to evaluate the validity and reliability of the assessment (Rust & Golombok, 2008; Warner, 2008).

Table 7

SDI 2.0 Motive Scales Descriptive Statistics

Test | Well Blue | Well Red | Well Green | Conflict Blue | Conflict Green | Conflict Red |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean | 36.6 | 31.6 | 31.8 | 29.0 | 27.0 | 44.0 |

Std. Dev | 10.4 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 12.4 | 11.3 |

Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Max | 100 | 100 | 93 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Skew | .397 | .150 | .475 | .468 | .431 | .382 |

Kurtosis | 1.437 | .762 | 1.232 | 1.074 | .721 | .862 |

n=9,798

Table 8

Strengths Portrait Ranking Descriptive Statistics

ID | Strength | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B1 | Supportive | 9.9 | 6.5 | 1 | 28 | 0.586 | -0.426 |

B2 | Caring | 11.1 | 7.1 | 1 | 28 | 0.456 | -0.754 |

B3 | Devoted | 15.9 | 7.1 | 1 | 28 | -0.196 | -1.179 |

B4 | Modest | 13.5 | 8.4 | 1 | 28 | 0.131 | -1.179 |

B5 | Helpful | 11.6 | 7.0 | 1 | 28 | 0.320 | -0.921 |

B6 | Loyal | 12.1 | 6.6 | 1 | 28 | 0.227 | -0.784 |

B7 | Trusting | 17.0 | 7.5 | 1 | 28 | -0.331 | -0.900 |

R1 | Risk-Taking | 20.9 | 7.2 | 1 | 28 | -0.331 | -0.900 |

R2 | Competitive | 19.4 | 8.1 | 1 | 28 | -0.804 | -0.582 |

R3 | Quick-to-Act

| 16.1 | 7.9 | 1 | 28 | -0.335 | -1.100 |

R4 | Forceful | 20.1 | 7.4 | 1 | 28 | -0.994 | -0.112 |

R5 | Persuasive | 17.1 | 8.1 | 1 | 28 | -0.513 | -0.962 |

R6 | Ambitious | 18.2 | 7.9 | 1 | 28 | -0.513 | -0.962 |

R7 | Self-Confident | 13.9 | 8.0 | 1 | 28 | -0.022 | -1.235 |

G1 | Persevering | 15.2

| 7.3 | 1 | 28 | -0.227 | -1.000 |

G2 | Fair | 11.7 | 6.5 | 1 | 28 | -0.288 | -0.731 |

G3 | Principled | 14.0 | 7.4 | 1 | 28 | 0.001 | -1.084 |

G4 | Analytical | 14.0 | 8.4 | 1 | 28 | 0.035 | -1.300 |

G5 | Methodical | 13.4 | 8.1 | 1 | 28 | 0.053 | -1.202 |

G6 | Reserved | 16.8 | 9.0 | 1 | 28 | -0.353 | -1.274 |

G7 | Cautious | 14.9 | 7.6 | 1 | 28 | -0.074 | -1.061 |

H1 | Option-Oriented | 12.7 | 7.1 | 1 | 28 | 0.154 | -1.045 |

H2 | Tolerant | 11.7 | 6.7 | 1 | 28 | 0.387 | -0.722 |

H3 | Adaptable | 11.4 | 7.1 | 1 | 28 | 0.320 | -0.900 |

H4 | Inclusive | 12.6 | 7.2 | 1 | 28 | 0.183 | -0.979 |

H5 | Sociable | 13.7 | 8.9 | 1 | 28 | 0.088 | -1.410 |

H6 | Open-to-Change | 12.2 | 7.4 | 1 | 28 | 0.243 | -1.107 |

H7 | Flexible | 14.1 | 7.3 | 1 | 28 | 0.040 | -1.045 |

n=12,565

Table 9

Overdone Strengths Portrait Ranking Descriptive Statistics

ID | Overdone Strength | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B1 | Self-Sacrificing | 9.4 | 7.4 | 1 | 28 | 0.691 | -0.610 |

B2 | Submissive | 14.1 | 7.6 | 1 | 28 | 0.033 | -1.191 |

B3 | Subservient | 16.2 | 7.8 | 1 | 28 | -0.226 | -1.101 |

B4 | Self-Effacing | 8.9 | 7.5 | 1 | 28 | 0.882 | -0.271 |

B5 | Smothering | 14.8 | 7.5 | 1 | 28 | -0.110 | -1.115 |

B6 | Blind | 12.7 | 6.8 | 1 | 28 | 0.202 | -0.859 |

B7 | Gullible | 15.2 | 8.1 | 1 | 28 | -0.038 | -1.247 |

R1 | Reckless | 18.6 | 7.8 | 1 | 28 | -0.565 | -0.845 |

R2 | Aggressive | 18.3 | 8.8 | 1 | 28 | -0.536 | -1.166 |

R3 | Rash | 12.4 | 7.6 | 1 | 28 | 0.285 | -1.086 |

R4 | Domineering | 17.4 | 8.3 | 1 | 28 | -0.339 | -1.185 |

R5 | Abrasive | 16.6 | 8.1 | 1 | 28 | -0.326 | -1.210 |

R6 | Ruthless | 19.9 | 7.4 | 1 | 28 | -0.888 | -0.279 |

R7 | Arrogant | 11.3 | 8.0 | 1 | 28 | 0.439 | -1.083 |

G1 | Stubborn | 11.2 | 7.0 | 1 | 28 | 0.384 | -0.922 |

G2 | Cold | 15.0 | 7.3 | 1 | 28 | -0.206 | -0.988 |

G3 | Unbending | 14.2 | 7.4 | 1 | 28 | -0.019 | -1.064 |

G4 | Obsessed | 13.5 | 7.9 | 1 | 28 | 0.103 | -1.102 |

G5 | Rigid | 13.9 | 7.8 | 1 | 28 | 0.030 | -1.174 |

G6 | Distant | 15.8 | 8.8 | 1 | 28 | -0.115 | -1.366 |

G7 | Suspicious | 15.3 | 8.3 | 1 | 28 | -0.117 | -1.286 |

H1 | Indecisive | 15.5 | 7.1 | 1 | 28 | -0.130 | -0.990 |

H2 | Indifferent | 14.6 | 7.6 | 1 | 28 | 0.009 | -1.167 |

H3 | Compliant | 11.4 | 7.0 | 1 | 28 | 0.393 | -0.880 |

H4 | Indiscriminate | 15.6 | 6.5 | 1 | 28 | -0.177 | -0.684 |

H5 | Intrusive | 15.9 | 8.2 | 1 | 28 | -0.264 | -1.129 |

H6 | Inconsistent | 13.8 | 7.1 | 1 | 28 | 0.042 | -0.955 |

H7 | Unpredictable | 14.7 | 7.2 | 1 | 28 | -0.069 | -0.970 |

n=12,565

In personality assessment, validity is about whether the results are true and accurate, while reliability is about consistency, or repeatability of the findings. Statistically speaking, the least important form of validity is face-validity, whether the respondent agrees with the results. However, face-validity is the most important aspect for users of the results. If the results are not presented in a way that rings true for the users, they will not accept or apply the results, and the assessment effort will be wasted.

Achieving face validity is an art with a scientific foundation. The SDI 2.0 uses valid and reliable data, along with grounded theory, to inform internally consistent descriptions of results that resonate for the users. The SDI 2.0 has extremely high face-validity. Respondents have a near universal acceptance of their results; it is rare to encounter a person who disagrees strongly with their SDI 2.0 results.

Table 10

Strength Means by MVS

ID | Strength | Blue MVS | Red-Blue MVS | Red MVS | Red-Green MVS | Green MVS | Blue-Green MVS | Hub MVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B1 | Supportive | 6.6 | 8.4 | 12.9 | 15.2 | 12.9 | 8.9 | 10.2 |

B2 | Caring | 6.9 | 8.7 | 14.6 | 18.1 | 15.1 | 9.7 | 11.5 |

B3 | Devoted | 12.7 | 15.7 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 17.5 | 14.2 | 16.5 |

B4 | Modest | 11.2 | 15.4 | 18.2 | 16.3 | 12.1 | 10.1 | 13.7 |

B5 | Helpful | 8.0 | 10.9 | 15.8 | 16.7 | 14.1 | 9.6 | 11.9 |

B6 | Loyal | 10.3 | 12.0 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 12.6 | 10.7 | 12.4 |

B7 | Trusting | 13.5 | 15.3 | 19.3 | 21.9 | 20.5 | 15.8 | 17.6 |

R1 | Risk-Taking | 22.9 | 19.0 | 15.8 | 17.4 | 22.2 | 23.8 | 21.0 |

R2 | Competitive | 22.7 | 18.3 | 13.9 | 14.1 | 19.6 | 23.2 | 19.1 |

R3 | Quick-to-Act

| 16.4 | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.9 | 17.6 | 18.0 | 16.5 |

R4 | Forceful | 23.1 | 19.3 | 14.0 | 14.5 | 20.2 | 23.6 | 20.1 |

R5 | Persuasive | 20.9 | 14.3 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 19.5 | 22.7 | 17.6 |

R6 | Ambitious | 20.9 | 17.6 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 18.5 | 21.5 | 17.9 |

R7 | Self-Confident | 17.5 | 12.9 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 13.0 | 17.8 | 13.5 |

G1 | Persevering | 17.3 | 16.0 | 13.6 | 12.4 | 13.3 | 15.4 | 15.1 |

G2 | Fair | 12.3 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 10.8 | 11.3 |

G3 | Principled | 14.5 | 15.8 | 15.1 | 12.7 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 13.9 |

G4 | Analytical | 16.8 | 18.0 | 15.5 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 11.9 | 13.4 |

G5 | Methodical | 15.7 | 17.2 | 14.4 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 11.8 | 13.0 |

G6 | Reserved | 16.4 | 22.0 | 22.5 | 17.1 | 11.4 | 11.3 | 16.9 |

G7 | Cautious | 15.5 | 20.2 | 20.2 | 13.5 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 14.5 |

H1 | Option-Oriented | 13.7 | 12.7 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 12.6 |

H2 | Tolerant | 10.8 | 12.7 | 14.0 | 14.2 | 11.6 | 9.8 | 11.7 |

H3 | Adaptable | 11.9 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 12.2 | 11.1 |

H4 | Inclusive | 11.2 | 10.0 | 12.8 | 15.6 | 15.5 | 14.2 | 12.5 |

H5 | Sociable | 12.4 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 16.8 | 18.4 | 17.2 | 14.0 |

H6 | Open-to-Change | 11.3 | 11.3 | 13.0 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 12.3 |

H7 | Flexible | 12.8 | 14.2 | 15.7 | 16.4 | 15.2 | 12.9 | 14.2 |

Table 11

Overdone Strength Means by MVS

ID | Overdone Strength | Blue MVS | Red-Blue MVS | Red MVS | Red-Green MVS | Green MVS | Blue-Green MVS | Hub MVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B1 | Self-Sacrificing | 5.8 | 8.1 | 13.4 | 15.3 | 12.5 | 7.6 | 9.5 |

B2 | Submissive | 9.9 | 13.7 | 18.1 | 19.8 | 16.9 | 11.5 | 14.7 |

B3 | Subservient | 12.8 | 15.7 | 18.9 | 20.1 | 18.5 | 14.0 | 16.8 |

B4 | Self-Effacing | 7.1 | 10.3 | 12.8 | 11.5 | 8.3 | 6.6 | 8.9 |

B5 | Smothering | 10.9 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 13.8 | 15.3 |

B6 | Blind | 10.9 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 15.6 | 13.9 | 11.9 | 13.1 |

B7 | Gullible | 11.8 | 13.0 | 17.2 | 19.8 | 18.9 | 14.7 | 15.6 |

R1 | Reckless | 20.5 | 16.8 | 14.1 | 15.6 | 19.7 | 21.8 | 18.6 |

R2 | Aggressive | 22.2 | 17.1 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 18.4 | 22.8 | 17.7 |

R3 | Rash | 12.2 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 13.0 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 12.6 |

R4 | Domineering | 21.6 | 16.1 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 16.9 | 21.9 | 17.0 |

R5 | Abrasive | 20.3 | 13.8 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 17.6 | 21.7 | 16.4 |

R6 | Ruthless | 23.0 | 19.8 | 14.0 | 14.3 | 19.5 | 23.0 | 19.8 |

R7 | Arrogant | 15.0 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 7.8 | 10.9 | 15.7 | 10.6 |

G1 | Stubborn | 14.2 | 11.6 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 12.8 | 10.6 |

G2 | Cold | 17.4 | 16.6 | 14.0 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 15.4 | 14.7 |

G3 | Unbending | 15.8 | 15.8 | 13.8 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 14.4 | 13.8 |

G4 | Obsessed | 14.9 | 16.7 | 15.1 | 11.8 | 9.8 | 11.4 | 13.2 |

G5 | Rigid | 16.2 | 17.6 | 15.0 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 12.3 | 13.5 |

G6 | Distant | 14.7 | 20.7 | 21.6 | 17.0 | 11.0 | 10.3 | 15.9 |

G7 | Suspicious | 15.8 | 19.7 | 19.4 | 13.7 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 15.1 |

H1 | Indecisive | 15.1 | 15.8 | 16.1 | 15.5 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 15.8 |

H2 | Indifferent | 11.9 | 16.3 | 18.7 | 18.4 | 14.1 | 11.0 | 14.9 |

H3 | Compliant | 10.3 | 11.2 | 13.2 | 13.7 | 11.8 | 10.4 | 11.4 |

H4 | Indiscriminate | 14.9 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 16.1 | 15.7 |

H5 | Intrusive | 14.3 | 12.3 | 14.5 | 18.6 | 19.1 | 17.8 | 16.3 |

H6 | Inconsistent | 12.3 | 13.0 | 14.5 | 15.9 | 15.2 | 13.4 | 14.0 |

H7 | Unpredictable | 13.5 | 15.4 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 15.5 | 13.1 | 14.5 |

The test-retest, or repeated measures, reliability of the SDI’s motives scales is +/- 6 points. This means that the majority of scale scores do not change enough to alter the basic understanding or interpretation of the results. However, there are some sets of scores that change on re-test more than the stated metric. This is normal for test-retest calculations. Table 12 reports the retest reliability measures from three studies. Porter’s (1973) study used the Pearsonian coefficient, while Barney’s (1998) and Cunningham’s (2004) studies reported Cronbach’s alpha.

The internal reliability of the motive scales is presented in Table 13, along with comparable data from an earlier study (Scudder, 2013). Both studies report the Cronbach’s Alpha values. Each item comprising the SDI scales was evaluated to determine the effect on the internal reliability of the scales if the item were deleted.

As shown in Table 14, the internal reliability of the scales would be reduced if any set of items was removed from the assessment. This indicates that every set increases the internal reliability. Two items (C16 Green and C20 Blue) would slightly raise the internal reliability if deleted. However, to do so would require the removal of the other in-set responses, which would decrease the overall internal reliability of the assessment.

Table 12

SDI Motive Scales Test-Retest Reliability

Test | n | Well Blue | Well Red | Well Green | Conflict Blue | Conflict Red | Conflict Green |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Porter (1973) | 100 | .78 | .78 | .76 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Barney (1998) | 106 | .85 | .84 | .83 | .87 | .81 | .82 |

Cunningham (2004) | 322 | .90 | .91 | .89 | .89 | .90 | .86 |

Table 13

Motive Scales Internal Reliability

Test | Well Blue | Well Red | Well Green | Conflict Blue | Conflict Red | Conflict Green |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Scudder, (2013) n=9,798

| .796 | .846 | .781 | .806 | .826 | .710 |

Present Study n=12,565 | .794 | .818 | .759 | .766 | .797 | .678 |

Table 14

Motive Scales: Alpha Values if Items Deleted

Well / Conflict Item | Well Blue | Well Red | Well Green | Conflict Blue | Conflict Red | Conflict Green |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

W1/C11 | .748 | .817 | .735 | .739 | .771 | .646 |

W2/C12 | .720 | .796 | .715 | .739 | .779 | .650 |

W3/C13 | .743 | .822 | .747 | .735 | .794 | .651 |

W4/C14 | .707 | .792 | .717 | .725 | .760 | .627 |

W5/C15 | .728 | .794 | .731 | .721 | .766 | .656 |

W6/C16 | .726 | .811 | .745 | .746 | .786 | .679 |

W7/C17 | .730 | .784 | .725 | .746 | .780 | .658 |

W8/C18 | .714 | .793 | .723 | .724 | .777 | .633 |

W9/C19 | .735 | .798 | .739 | .745 | .781 | .636 |

W10/C20 | .735 | .808 | .731 | .779 | .794 | .669 |

n=12,565

Relationship Intelligence and the SDI 2.0 take a whole-life, systems view of personality, and situate the deployment of strengths in a workplace context, based on respondents’ roles. The essence of a systems view is that the interaction between elements, such as motives and strengths, is just as important, if not more important, than the elements themselves. The systems view sharply contrasts with approaches to understanding people that isolate variables, and identify traits or types without accounting for emotional states or contexts in which respondents have self-determination. These reductionist approaches result in limiting, impractical measures that may have statistical validity, but lack real-world utility because they do not reflect the true complexity of human experience.

Each of the four views: Motivational Value System, Conflict Sequence, Strengths, and Overdone Strengths, connects with the other three. Figure 7 identifies four of the clearest connections, which are often used in training and development efforts that include the SDI 2.0. The MVS is part of core personality. People’s drives, motives, and values influence the way they choose to deploy their strengths at work. The use of strengths at work is most authentic when people deploy their strengths for an underlying reason that resonates with their MVS.

Strengths deployed in relationships at work do not always have the intended effect. This opens up connections with the concept of overdone strengths and consideration of whether the strength was appropriately applied to the task or relationship.

The focus on relationships includes consideration of how strengths are perceived by others. When perceived as overdone, it may trigger conflict in the relationship. Conflict Triggers may also originate with the MVS as events restrict people’s motives or go against their values.

The Conflict Sequence is part of core personality, but under a different emotional state than the MVS. Motives during conflict are directed toward addressing the issue at hand in a way that results in resolution and a change to people’s emotional states, such that they are working from their MVS again once the conflict is resolved.

The independent variables within the SDI 2.0 produce virtually limitless combinations, which in turn produce deeply personalized reports for respondents. Sound academic theory, coupled with a long history of empirical support, enable the reporting and application of SDI 2.0 results to blend art and science. The methodology of the SDI 2.0 ensures that users receive rich, textured descriptions of personality and strengths at work, which can be applied with confidence to improve the quality of working relationships.

Figure 7

Summary Connections Between Four Views Provided by SDI 2.0

An Examination of the Theoretical Roots and Psychometric Properties of the Strength Deployment Inventory. (Masters of Philosophy Thesis), Aukland University, Aukland, NZ.

Strength Deployment Inventory: Reliability and validity executive summary. California School of Professional Psychology. Alliant International University. San Diego, CA.

Libidinal Types. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 1(1), 3-6.

Man for Himself: An inquiry into the psychology of ethics. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

A Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: McGraw-Hill. Livson, N. H., & Nichols, T. F. (1957). Discrimination and Reliability in Q-sort Personality Descriptions. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52(2), 159-165.

Outline of a Conception of Personality. In C. Kluckhohn & H. A. Murray (Eds.), Personality in Nature, Society, and Culture (pp. 3-32). New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf.

Personality Theories (Sixth ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

The Questions of Drive vs. Motive in Psychoanalysis: A modest proposal. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57(4), 807-845.

Character as Self-Organizing Complexity. Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, 23, 3-34.

An Introduction to Therapeutic Counseling. Cambridge, MA: The Riverside Press.

Strength Deployment Inventory: First manual of administration and interpretation. Pacific Palisades, CA: Personal Strengths Assessment Service.

On the Development of Relationship Awareness Theory: A personal note. Group & Organization Management, 1(3), 302-309.

Client Centered Therapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

On Becoming a Person. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.Rosenberg, A. (2008)

Philosophy of Social Science (3rd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Modern Psychometrics (Third ed.): Routledge.

Personality Types in Relationship Awareness Theory: The validation of Freud’s libidinal types and explication of Porter’s motivational typology. (Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation), Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara.

SDI 2.0 Strength Deployment Inventory 2.0. Carlsbad, CA: Personal Strengths Publishing.

The Study of Behavior: Q-technique and its methodology (Midway reprint ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Applied Statistics: From bivariate through multivariate techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Handbook of Personality Assessment. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

SDI 2.0 Methodology and Meaning. Carlsbad, CA: Personal Strengths Publishing.