“Words, words, words.” –Hamlet

Simply put, management is about getting things done. At times, it’s the manager taking action, but most often, it’s the manager motivating others to take collective action. And the manager generally does this through one common yet powerful medium: words.

Written or spoken, words are the manager’s most important tool. How well this tool is used determines nearly every measurable outcome—everything from the engagement level of employees to the team’s results and even the manager’s own career trajectory.

If this is the case, as I believe it is, why do we spend relatively little time considering how the words we use impact—or fail to impact—others? Most managers I know are deluged with a daily avalanche of words. In fact, one study suggests that managers spend between two-thirds and three-fourths of their day in conversation.

No matter where you work, unless maybe you’re a lighthouse keeper, it’s likely that you spend the vast majority of each day talking or listening. It’s the way we gather information, stay abreast of projects, identify problems, give feedback, make decisions, define strategy, update superiors, and virtually everything else that determines success or failure in organizational life. In short, it’s how we get stuff done.

If management is about getting things done, and communication is how we get stuff done, then shouldn’t managers focus on communication?

Paul Fireman seemed to think so. The longtime Reebok CEO believed that all action occurred through a “network of conversations.” Fireman said, “If you want to find out what’s going on in the organization, all you have to do is listen to the conversations in the hallways. That will tell you more than any report or formal control system can.” He also believed that the only way to create lasting change is to “go out and start having a new kind of conversation … and keep having it until you start hearing a different kind of talk.”

These facts reinforce my point. Communication—the way we use words—is the manager’s most important tool. So what would it look like if we all took managerial rhetoric more seriously? What if we focused on how we might use language to inspire others to bring their best every day? What if the words we chose actually prevented conflict instead of inciting it?

Choosing and using words more effectively requires us to ask and answer three critical questions:

1. Who’s my audience?

Harvard Business School professors, Robert Eccles and Nitin Nohria, argue that organizations need to be understood as collections of people who say and do particular things, rather than just employees, human resources, or even human assets. Likewise, strategically choosing one’s words based on the recipient almost always works better than a generic, one-size-fits-all message or more commonly, the manager’s preferred style of communication.

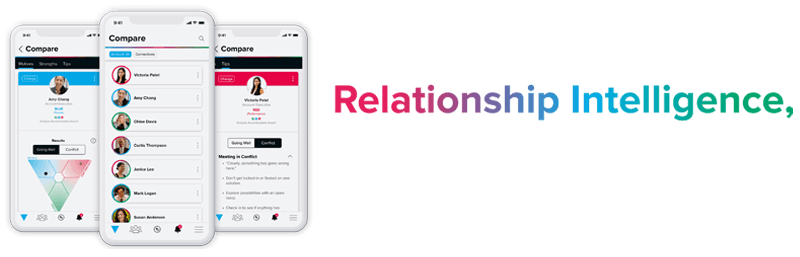

On the surface, it might seem incredibly difficult to discover what’s unique about each member of the team—especially if you want to go beyond the superficial—and then tailor a message that addresses their particular needs. I have found the Strength Deployment Inventory (SDI) to be the most powerful tool for uncovering what drives people and how to interact with them most productively. In a few hours of focused and facilitated interaction, people can learn more about what really matters to their colleagues and how to best connect with them, than they could through years of casual conversation.

2. How do I honor what’s important to them?

Sociologist Carol Heimer believes that particularism involves two elements: understanding all of the components that make up a person’s identity (i.e., personality traits, drives, strengths, and weaknesses) and how that identity affects their relationships. Effective management takes into account the identity of each employee and values it. The best management training, then, focuses on understanding the identity of people. You can’t honor what you don’t understand.

3. What adjustments do I need to make to ensure my message is heard?

If you know your audience and are ready to practice particularism, it will likely require some stylistic adjustments. The good news is that we all have a wide array of strengths that we can choose and use to have a positive impact on people. Most people rely on only a few strengths, so learning to access less familiar strengths can be a powerful asset when trying to communicate with members of your team who see things differently.

Communication is a manager’s most important tool. Are you attuned to what you’re saying and what others are saying? Is your message getting through? Remember, words matter.